Chelated Magnesium vs. Non-Chelated Magnesium: Which One Should You Choose?

Magnesium, the marvelous mineral, has become a go-to supplement for many people seeking to improve their overall health. But with so many types and forms of magnesium on the market, how do you know which one is right for you? The battle often comes down to chelated magnesium vs. non-chelated magnesium. Let's explore the differences, the science behind them, and how to make the best choice for your body.

What Is Magnesium, and Why Is It Important?

Magnesium is an essential mineral that plays a crucial role in over 300 enzymatic reactions in our bodies. It's vital for muscle function, nerve function, energy production, and even maintaining healthy bones and teeth (1,2). Unfortunately, many of us don't get enough magnesium through our diets, leading to a deficiency that can result in fatigue, muscle weakness, and irritability (3).

What Is Chelated Magnesium?

Chelated magnesium is a form of magnesium that has been chemically bonded to another molecule, typically an amino acid or another organic compound, to create a more stable and absorbable compound (4,5). This process, known as chelation, can improve the bioavailability of magnesium, making it easier for your body to absorb and use (6). Common forms of chelated magnesium include magnesium glycinate, magnesium malate, and magnesium citrate.

How Is Chelated Magnesium Different from Non-chelated Forms of Magnesium?

Absorption and Bioavailability

The key difference between chelated magnesium and non-chelated forms of magnesium lies in their absorption rates and bioavailability. Chelated magnesium has been shown to have superior absorption compared to non-chelated forms, such as magnesium oxide or magnesium sulfate (7,8). This is because the chelation process helps the magnesium to bypass the gut and enter the bloodstream more efficiently (9).

Side Effects and Tolerance

Another notable difference between chelated magnesium and non-chelated forms of magnesium is their potential side effects. Some non-chelated forms of magnesium, particularly magnesium oxide, can cause gastrointestinal upset, including diarrhea and abdominal cramps (10,11). Chelated magnesium, on the other hand, is often better tolerated and less likely to cause these side effects, making it a more comfortable option for those with sensitive stomachs (12).

What Does the Science Say About Chelated Magnesium vs. Non-Chelated Magnesium?

Several clinical studies have compared the efficacy of chelated magnesium to non-chelated forms of magnesium. One study found that magnesium glycinate, a chelated form, had a higher bioavailability and was better absorbed than magnesium oxide, a non-chelated form (13,14). Another study showed that magnesium malate, a chelated form, had superior bioavailability compared to magnesium sulfate, a non-chelated form (15).

While more research is needed, these studies suggest that chelated magnesium may offer some advantages over non-chelated forms of magnesium in terms of absorption and tolerability.

So, Which One Should You Choose?

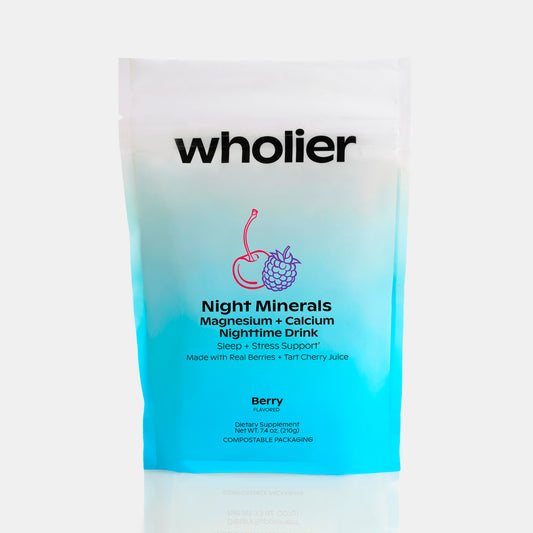

When it comes to the choice between chelated and non-chelated magnesium, the ultimate decision hinges on individual needs and preferences. However, a compelling case can be made for chelated magnesium, given its superior absorption and potentially fewer side effects. While non-chelated magnesium could certainly be an adequate option for some, the benefits of chelated magnesium are often found to be more compelling for the majority of people. Given the better bioavailability and tolerance profile, chelated magnesium generally stands as the preferred choice. That's why our Night Minerals Magnesium and Calcium Drink contains two chelated forms of magnesium, rather than less bioavailable non-chelated forms.

Sources:

(1) de Baaij, Jeroen H. F., Joost G. J. Hoenderop, and René J. M. Bindels. "Magnesium in man: implications for health and disease." Physiological reviews 95, no. 1 (2015): 1-46.

(2) Swaminathan, R. "Magnesium metabolism and its disorders." The Clinical Biochemist Reviews 24, no. 2 (2003): 47-66.

(3) DiNicolantonio, James J., James H. O'Keefe, and William Wilson. "Subclinical magnesium deficiency: a principal driver of cardiovascular disease and a public health crisis." Open Heart 5, no. 1 (2018): e000668.

(4) Effros, R. M., and R. B. Swenson. "Chemistry and clinical use of chelating agents." Annual review of medicine 22, no. 1 (1971): 115-130.

(5) Gümüş, H., and H. M. Scrimgeour. "Chelated minerals: Are they worth the extra cost?." Dairy Herd Management (2016).

(6) Coudray, Charles, Jean‐Paul Rambeau, Christine Feillet‐Coudray, Eric Gueux, Christian Tressol, Monique Mazur, and Yves Rayssiguier. "Study of magnesium bioavailability from ten organic and inorganic Mg salts in Mg‐depleted rats using a stable isotope approach." Magnesium research 18, no. 4 (2005): 215-223.

(7) Schuette, Scott A., William R. Lachenbruch, and Henry C. Lukaski. "Bioavailability of magnesium diglycinate vs magnesium oxide in patients with ileal resection." Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition 18, no. 5 (1994): 430-435.

(8) Lindberg, J. S., W. D. Zobitz, S. R. Poindexter, and Charles Y. C. Pak. "Magnesium bioavailability from magnesium citrate and magnesium oxide." Journal of the American College of Nutrition 9, no. 1 (1990): 48-55.

(9) Walker, A. F., G. Marakis, S. M. Christie, and C. Byng. "Mg citrate found more bioavailable than other Mg preparations in a randomised, double-blind study." Magnesium research 16, no. 3 (2003): 183-191.

(10) Ranade, Vasant, and Charles F. Somberg. "Bioavailability and pharmacokinetics of magnesium after administration of magnesium salts to humans." American journal of therapeutics 7, no. 5 (2000): 345-357.

(11) Coudray, Charles, Christine Feillet-Coudray, Eric Gueux, Christian Tressol, Monique Mazur, and Yves Rayssiguier. "The effects of inorganic and organic magnesium salts on intestinal absorption of magnesium in rats." Magnesium research 12, no. 3 (1999): 187-192.

(12) Firoz, Mansoor, and Michael Graber. "Bioavailability of US commercial magnesium preparations." Magnesium research 14, no. 4 (2001): 257-262.

(13) DiNicolantonio, James J., James H. O'Keefe, and William Wilson. "Subclinical magnesium deficiency: a principal driver of cardiovascular disease and a public health crisis." Open Heart 5, no. 1 (2018): e000668.

(14) Schuette, Scott A., William R. Lachenbruch, and Henry C. Lukaski. "Bioavailability of magnesium diglycinate vs magnesium oxide in patients with ileal resection." Journal of Parent